If we were to send this image to the printer at 200DPI, the physical size would be correct at 8x10”. However, if we sent it at 300DPI with no scaling, the resulting image would measure smaller—5.3x6.6” to be precise. Affinity Photo’s New Document dialog, toggling. Affinity Photo is an incredibly powerful program, but it can be overwhelming at first. To help you jumpstart your photo editing skills, I put together this list of the best tips and tricks. Whether you have used Affinity Photo for an hour or a year, I hope you find this list to be valuable. For most image editing workflows, however, you would start by loading your image. An intuitive approach to this is simply to click-drag your image file onto Affinity Photo’s interface and release the mouse button. A new document will be created from the image using its initial pixel resolution (e.g.

Affinity Photo puts a large amount of image editing power at your fingertips, but it has a few notable differences to other image editing applications that you should know if you want to make the most of its feature set. We’re going to look briefly at the user interface, then explore developing a RAW file and performing some non-destructive image edits which we can revisit later.

Before continuing, if you want to download the practice file we’ll be using later for the image edit, you can grab it here:

Getting started—new document or open image?

Unlike Affinity Designer or Affinity Publisher, your approach to what we might call a ‘new document’ will typically differ for most workflows. You don’t tend to start with a blank document—rather, you open an existing image or RAW file, and that dictates the dimensions and other attributes of the document.

That said, creating a new document is perfectly valid for some workflows—compositing, print work like posters and CD/DVD covers to name a few examples. You would usually create a blank document whenever you need to match specific dimensions.

For most image editing workflows, however, you would start by loading your image. An intuitive approach to this is simply to click-drag your image file onto Affinity Photo’s interface and release the mouse button. A new document will be created from the image using its initial pixel resolution (e.g. 6000x4000).

If you load in a RAW file, however, that’s when Affinity Photo switches to its Develop Persona, which segues nicely into the following explanation about Personas!

Personas

The concept of Personas exists across all the Affinity apps—essentially, Personas are different workspaces for different tasks. In truth, the majority of your time will be spent in the Photo Persona and, if you develop RAW files, the Develop Persona. The other Personas are for additional functionality that you may or may not require.

Here’s a quick breakdown of each Persona’s purpose:

Photo Persona

This Persona is where most of your time will be spent. It’s the main image editing workspace and gives you quick access to all the main tools, adjustments, filters and other functionality you’ll need.

Liquify Persona

The Liquify Persona is a dedicated workspace for mesh distortion work, giving you a full-screen layout in which to distort the image using a variety of tools.

For localised editing, you can use the Freeze Tool to prevent certain areas of an image from being distorted, then use the Thaw Tool once you have finished.

Develop Persona

This Persona is opened by default when you load a RAW file. It provides an intuitive, slider-based layout for making initial adjustments to your RAW image before you develop it and move to the Photo Persona for more in-depth (and non-destructive) editing using layers.

You can, however, enter this Persona from any valid pixel layer, meaning you can take advantage of it when you need to make quick adjustments.

Tone Mapping

The Tone Mapping Persona is used for ‘floating point’ HDR (high dynamic range) documents. It maps bright, out-of-range pixel values into standard dynamic range where a typical display or monitor can represent them.

You’ve typically come across this if you’ve ever merged bracketed exposures together to overcome a camera’s dynamic range limitation for challenging scenes (e.g. shooting directly into a sunset or on a very bright day with lots of contrast).

Like the Develop Persona, you can also jump into this Persona with any valid pixel layer selected—the Local Contrast feature can be used to add structure or texture to any image regardless of whether it has been merged to HDR.

Export Persona

This gives you detailed, fine-grained control over exporting regions of your document or image. Most image editing workflows will not need to use this Persona (File>Export will suffice for most people), but it’s invaluable for UI/Web design and compositing work where you might hand off isolated layers as images for other software.

If you’ve ever used a certain ‘Save As Layers’ feature, this would be your closest equivalent. You can hand-draw ‘slices’ or create them from layers and export them individually. You have full choice over the export format and other options for each separate ‘slice’.

Once exported, enabling ‘Continuous Export’ allows these slices to be continually re-exported and updated in the background as you work further on your document.

Tools

Each Persona has its own set of tools, but you’ll primarily be using the tools in the Photo Persona to fine-tune image edits using brushwork, cropping, transforming and retouching. These tools are all bound to a sensible and conventional layout of keyboard shortcuts. Here are a few examples of common tools you would need to use:

Move ToolV|Crop ToolC|Selection Brush ToolW|Flood Select ToolW|Flood Fill ToolG|Paint Brush ToolB|Clone Brush ToolS|Healing Brush ToolJ|Inpainting Brush ToolJ|Zoom ToolZ|

Note that some tools are bound to the same key (e.g. selection tools on W)—repeating the key will cycle through these tools.

Toolbar

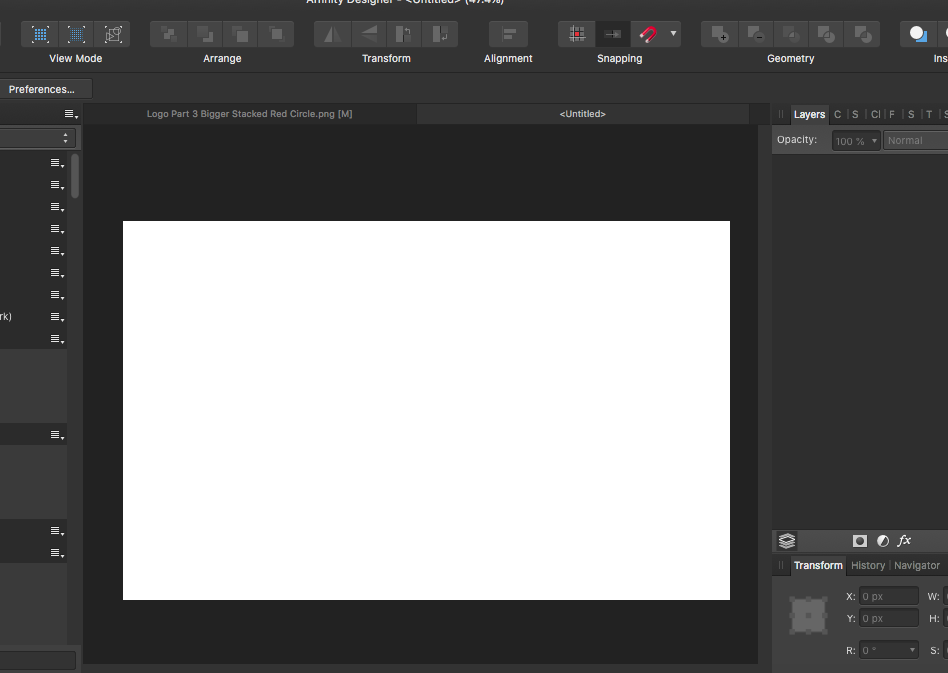

At the top of the user interface is the toolbar—this provides quick access to useful functionality like automatic corrections (levels, contrast, colours and white balance), selection tools such as quick masking, snapping configuration and geometric operations (clipping layers inside other layers). It also contains the Assistant Manager, which enables you to configure default behaviours for operations like adding mask layers and live filter layers (e.g. whether to clip inside the current layer).

If you’re a beginner and the terminology is beginning to scare you off, don’t worry—much of this functionality is not required to begin with and as you gradually learn how to use it, at least you’ll know where it is!

Studio Panels

Let’s talk about one final concept before we jump into editing an image. Affinity Photo has a wealth of functionality, but not all of it is immediately visible. This is because the app starts you off with a lean, uncluttered user interface. You have the tools on your left, the toolbar at the top and then a collection of panels on the right, collectively referred to as a Studio.

These panels provide functionality like a histogram, layers stack, brushes categories, colour creation and editing, undo history and channel manipulation.

All of these are staples of a typical image editing workflow, but you can expose additional panels which give you access to features like macros (recordable actions), global clone sources, character and paragraph controls for text, reusable assets (that you can create from any layer type) and scopes (e.g. a vectorscope, RGB parade, intensity waveform).

To see these additional panels, you can enable them from View>Studio at the top of the interface.

Editing an image—starting from RAW

Let’s take a look at a straightforward edit of a RAW file to ease us into the image editing process in Affinity Photo. We’ll do some very basic RAW development, then move to the Photo Persona for some more advanced, non-destructive editing, exploring some useful techniques along the way.

In case you missed it at the start of the article, here’s a download link for the RAW file we’ll be using so you can follow along:

Opening and editing the RAW file

With Affinity Photo, we can either go to File>Open, navigate to the RAW file and open it, or we can drag-drop the RAW file from a file explorer (e.g. Explorer on Windows, Finder on macOS) onto the user interface.

Here’s what the RAW image will initially look like—don’t worry, it was intentionally underexposed. You can see how lean the user interface is by default as well.

We’re actually going to do very little work in the Develop Persona. Although you can do as much processing as you want for your own imagery, for this example we’re going to use some minor adjustments to shape the initial look and then edit it further in the Photo Persona.

Here are the adjustments we’re going to make:

- On the Exposure category, move the Blackpoint slider all the way left to -10%.

- On the Shadows & Highlights category, move the Shadows slider to 50%.

- On the same category, move the Highlights slider to -40%.

There we go—told you they were minor adjustments! All we’re trying to do here is flatten out the image tonally by bringing up the shadow tones and ensure we’re recovering some highlight detail as well. Click the blue Develop button in the top left (just beneath the Persona icons) to ‘develop’ the image and move to the Photo Persona. The resulting image looks like this:

Before we move on, let’s quickly examine what effect the adjustments had on the image:

- The Blackpoint changes where absolute black is within the tonal range of the image. By moving it into negative values, we can raise the black level and reduce the apparent contrast within the darker areas of the image.

- The Shadows slider can enhance or reduce shadow detail. In most cases, we would use it to boost shadow detail in underexposed images, whether accidentally or intentionally underexposed to capture more highlight information.

- The Highlights slider can recover (negative values) or intensify (positive values) highlights in the image. Be careful when recovering highlights, however—on images where the highlights are clipped you may end up with halo artefacts around the brightest areas. The image we’re using is a great example of this, as bringing the slider any lower than -40% would exhibit this issue.

Saving your work

Before we start any major editing, it’s a good idea to save your work so far as an Affinity Photo (.afphoto) document. If you’ve used other image editing software, you’ll be familiar with the concept of saving into its native document format: it retains the layers you’ve created and is necessary to maintain a non-destructive workflow where you can revisit work at a later date and make changes to it.

To save your image as a document, go to File>Save As… and a file dialog will open. Navigate to a storage volume/disk and a directory of your choice, name the file, then click Save.

Tip: It’s a good idea to maintain backups of your work, whether that’s achieved manually or by an automatic process. Cloud storage is a great option: I use Dropbox and have a dedicated folder plus sub-folders for all of my Affinity Photo documents. This ensures they are all backed up with an additional version history, which is useful for rolling back to earlier versions if required.Working with layers and retouching

We’re now in the main Photo Persona—this means we can really dive in and tackle some deeper editing techniques.

Before we do any kind of tonal work, we’re going to tidy up and retouch the image. Thankfully there’s not much to do here, but there’s a little bit of lens flare on the right-hand side in the shadow areas:

We can easily remove these using the Inpainting Brush ToolJ. To select this tool, we need to access the retouching tools flyout from the tools on the left. Long-click on the Healing Brush Tool to produce the flyout, then hover over the Inpainting Brush Tool and release the mouse button to select it.

Alternatively, you can also precision click on the triangular shape at the bottom right of the tool icon. You can also double click the tool icon. Both of these methods will produce the flyout without you having to hold the mouse button down whilst you select the appropriate tool.

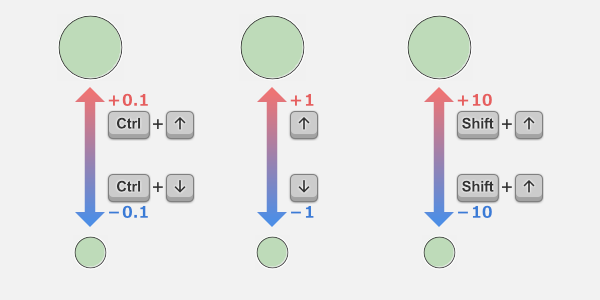

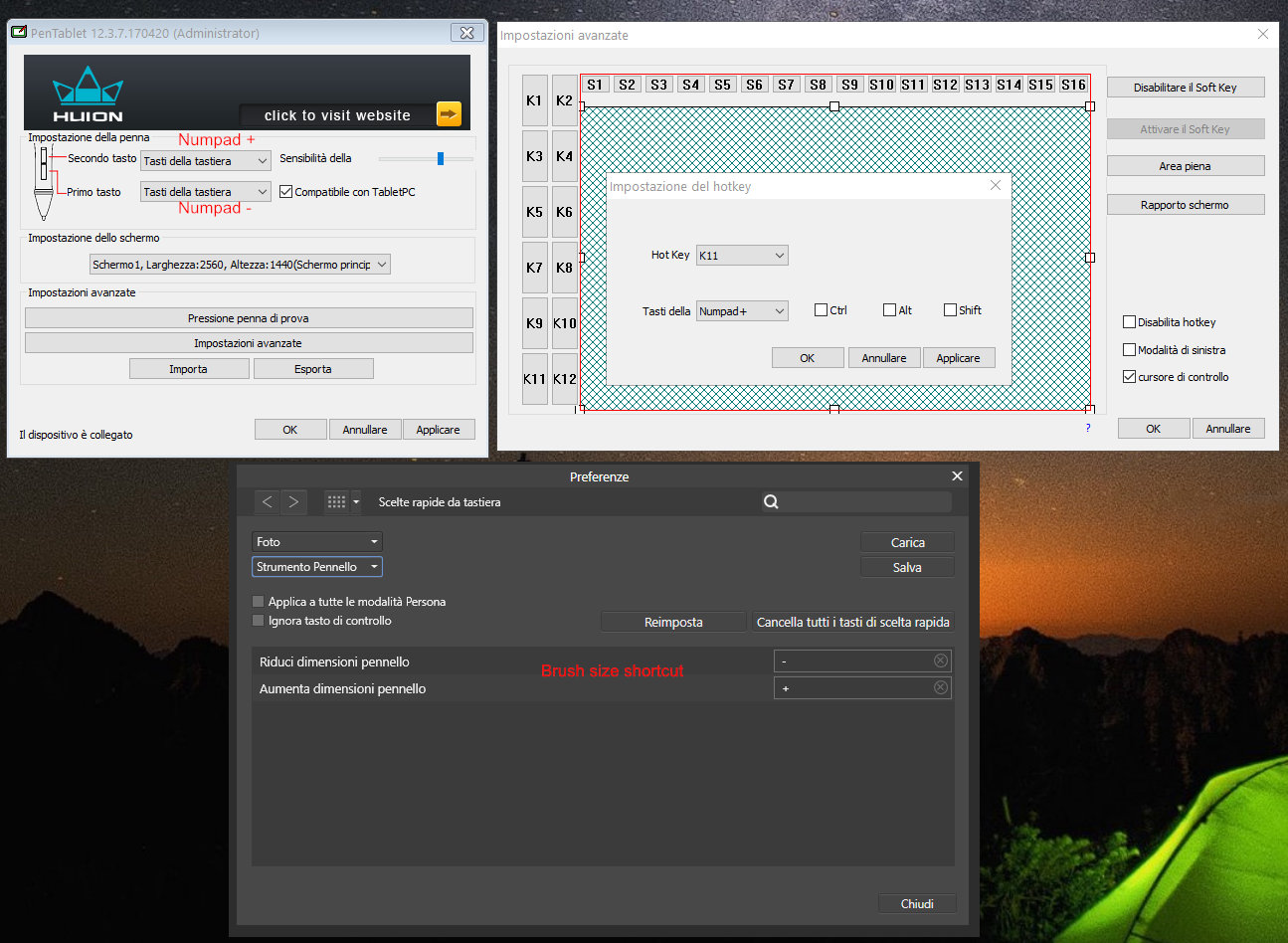

To use the Inpainting Brush Tool, we simply need to click-drag over areas of the image we want to replace, then release the mouse button. Don’t forget to set an appropriate Width before brushing: you can do this either via the Context Toolbar at the top (underneath the Persona icons) or by using the [ and ] bracket keys. I set my brush width to around 270px.

Tip: If you prefer to use the keyboard and mouse modifier to change brush width and hardness, you can do that too. On macOS, hold Ctrl+Option then hold left-click and drag. On Windows, hold Alt, then hold down the left and right mouse buttons and drag.After brushing over the lens flares, you’ll see them disappear. But wait! You’ll notice that we’ve effectively ‘overwritten’ the pixel information in this area. What if we wanted to change the result at a later date, or even after we’ve closed down and reopened the document? That’s where the concept of non-destructive editing comes in, and there are many different ways to achieve this. We’ll start by putting the retouching results on their own pixel layer.

- First, undo the inpainting by going to Edit>Undo, or using CMD+Z (macOS) / Ctrl+Z (Windows).

- Now click on the Layers Panel on the right-hand side. You’ll see one layer called Background—this is your image.

- Add a new pixel layer above this layer—to do this, click the Add Pixel Layer icon. Alternatively, you can use Layer>New Layer from the top menu or use the keyboard shortcut Shift+CMD+N (macOS) / Shift+Ctrl+N (Windows).

- With this new pixel layer selected, find the dropdown option that says Current Layer on the context toolbar. Change this to Current Layer and Below.

- Now brush over the lens flare areas again and you’ll see they have been removed and replaced by surrounding content.

- This time, however, the inpainting result has been put on the newly-created Pixel layer.

This option effectively lets the Inpainting Brush Tool sample from layers beneath the currently selected layer. This enables us to have a new pixel layer selected, but the inpainting will sample from the Background layer beneath (which is our image). The result will be put on the pixel layer we have selected. With this approach, we can perform all retouching non-destructively because the original image content is no longer being changed. At a later date, we can always delete that pixel layer and recreate the result if the inpainting needs some revision.

You can use this technique for multiple retouching and selection tools: these include the Clone Brush Tool, Healing Brush Tool, Patch Tool, Inpainting Brush Tool, Flood Fill Tool and the Flood Select Tool.

Tip: Stay organised with your layers by naming them: simply click into the text label next to the layer’s thumbnail, rename it, then hit return on the keyboard. We can name the Pixel layer ‘Inpainting’ in this case, since it contains the lens flare removal inpainting result.Tonal adjustments

At this point, we’ll look at making some tonal adjustments, namely adding some contrast and saturation to our image.

To achieve this, we’re going to use adjustment layers—these sit in the layer stack above the layers you wish to affect (or clipped into them), and we can perform a wide array of manipulations to both tone and colour.

Curves

First, let’s use a Curves adjustment. You’ll want to add this above the Pixel layer we’ve created for the inpainting—ensure this layer is selected first, then go to Layer>New Adjustment Layer>Curves.

The adjustment layer will be added, and a Curves dialog will appear with a graph: this represents the tonal range of your document. To the left is absolute black, and to the right is absolute white. You can click-drag to add nodes to the graph, and this allows you to shape the tones in a non-linear fashion.

See the diagram for an indication of how I’ve used the graph: I’ve added three nodes to bring the darker tones down, a middle node just slightly below the centre point, then a node near the top right to intensify the brighter tones. This adds a significant amount of contrast and ‘punch’ to the image.

Once you’ve finished editing the curves graph, simply close the dialog down. The beauty of adjustment layers is that you can double-click them and change their settings at any point—even after you’ve saved, closed down and re-opened your document.

Next, we’ll add some saturation to particular colour ranges in the image. Subtlety is key here as we don’t want to ‘overcook’ the vibrancy of the image too much.

HSL

To saturate (or desaturate) particular colour ranges, we can use an HSL adjustment. Let’s add one above the Curves adjustment by going to Layer>New Adjustment Layer>HSL.

The HSL adjustment gives you control over Hue shift, Saturation intensity and Luminosity—we’re only going to make use of the Saturation slider for now. You can target colour ranges or all colours cumulatively, and we’ll use the latter to increase the intensity of the reds and yellows.

Select the Reds colour range by clicking on the circular red icon underneath the colour wheel, then bring the Saturation shift slider up to 20%.

Now move across to the Yellows and increase the Saturation shift to 10%. We’re using a smaller amount here to avoid the grass looking too radioactive!

As we did before with the Curves adjustment, close the HSL dialog when you’re finished editing. The image should be looking quite compelling so far:

Dodging and burning

Dodging and burning is a popular technique to ‘relight’ areas of an image by lightening or darkening them. Rather than use the destructive Dodge Brush and Burn Brush tools, however, we’re going to employ another non-destructive technique using layers and blend modes.

Like we did with the non-destructive inpainting, create a new pixel layer using the Add Pixel Layer option. If you followed the tip above regarding naming your layers, you can do the same here and name the layer ‘Relighting’.

Before we start painting on it, we’re going to change both the Blend Mode and the Opacity of the layer in advance—this helps us to visualise the effect we want straight away whilst we’re painting.

Click the Blend Mode dropdown (where it says ‘Normal’ by default) and choose the Overlay blend mode. Now click on the arrow next to the 100%Opacity value and move the slider until it reads 35%.

Tip: Rather than single clicking, you can also click-drag on the Opacity arrow, move the slider to set the value, then release the mouse button.We’re now ready to begin painting: from the tools on the left, select the Paint Brush ToolB and on the context toolbar change the Hardness to 0%.

We’ll also need to set an initial brush width. You can do this on the context toolbar too using the Width option, but you can also use [ and ] to decrease and increase the width respectively. For painting on this image, I’d recommend a brush width of around 1000px.

The final preparatory step is to ensure we have a pure white colour set before painting: click onto the Colour panel located at the top right of the user interface. Chances are the active colour is set to pure black. Luckily, you have two colour ‘wells’ that you can quickly toggle between. Either press X on the keyboard or click the white circle underneath the black circle to toggle them. Your active colour should now be white.

We can now begin painting! What we’re going to do is produce a very subtle brightening of the main path leading down towards the sunset in the composition. Click-drag over the stone path and surrounding areas of grass and you will see them brighten.

If you go too far into the grass on the left or the mountains on the right, switch to the Erase Brush ToolE to erase away from the brush strokes you’ve just created. Don’t forget to check the Hardness of the Erase Brush: chances are it’s at the default value of 80%, so you’ll want to bring it down to 0% for a soft-edged brush.

Tip: Don’t be shy about experimenting with the Blend Mode and Opacity values when it comes to adding brushwork to an image. Overlay is great for non-destructive dodging with white and black colours, but you can use Reflect, Glow and Colour Dodge to enhance areas in an image such as reflections and artificial lighting. Just pick a blend mode, choose a suitable colour on the Colour panel and give it a try! Keep the Opacity value quite low, to begin with, then increase it until you find a good result.Sharpening

It’s time to put the finishing touches on our image in the form of sharpening. As with everything we’ve done so far, we’re going to apply sharpening non-destructively—to do this, we’ll add a live filter layer.

With any layer selected (typically the Relighting layer we’ve been working on), go to Layer>New Live Filter Layer>Sharpen>Unsharp Mask. This will add a live Unsharp Mask layer to our document.

There’s one issue, however: the layer appears to be nested into whichever parent layer we had selected. We call this child layering. This is intended behaviour for performance considerations, designed to limit the use of live filter layers rendering above many other layers. In this instance, however, it’s not going to have much effect if it’s restricted to the Relighting layer (or any other layer, for that matter, other than the image Background layer).

To remedy this, we can simply click-drag the Unsharp Mask layer and bring it to the top of the layer stack, then release the mouse button.

On the Unsharp Mask filter dialog, we’re interested in the Radius and Factor sliders.

Radius determines the number of pixels that are affected around the edge detail being sharpened. Low values such as 1-5px are great for fine detail sharpening, whereas larger values up to 100px will start to enhance what’s known as local contrast. Enhancing local contrast can increase perceptual sharpness, but be careful as it can result in haloing around edge detail.

Factor simply dictates the amount of sharpening to be applied. For this image, I’ve decided that a Radius of 2px and also a Factor of 2px will produce a nice, crisp looking image.

Exporting

Once we’ve completed the edit of our image, it’s time to export it and share it with others!

To do this, go to File>Export. This will present you with an export dialog and a number of export formats along the top.

Let’s keep things straightforward and go with JPEG—this is a universally supported format that will open just about anywhere. Although you can tweak the Quality slider to produce a smaller file size, I would only recommend this if you need to actually consider file size (e.g. if you are hosting images on your own website). Even when you are sending images via email, most email clients will automatically resample and compress images anyway.

That said, there is no harm in changing the quality to 99 rather than 100—this will result in very little or negligible quality loss and will dramatically reduce the file size. When you’re ready, click Export, navigate to a folder, type your file name if you wish to rename the image, then click on the Save button.

Job done—we’ve now exported the image and it’s ready to be shared or archived (hopefully both!).

Tip: If you want to archive your completed images, consider using a lossless format like TIFF rather than JPEG which is lossy. Affinity Photo offers compression options for TIFF to help reduce file size.An archive of lossless files such as TIFFs will prove incredibly useful should you ever lose the original Affinity Photo documents. Lossless simply means that no pixel data is ‘compromised’ in order to achieve more efficient compression, so it’s the best way to ensure you have the highest quality versions of your exported images.Further support

Hopefully, this has given you a comprehensive introductory insight into Affinity Photo: there’s so much to learn, and though it may seem daunting at first it can also be incredibly exciting.

We produce a wealth of support content, including a cheat sheet for keyboard shortcuts, many video tutorials and more articles on this site. Here’s a quick list:

- Video tutorials on YouTube and the Affinity website

- Learning articles on Affinity Spotlight

Additionally, our official support forums are a great place to ask questions, and you’ll find a Tutorials subforum with both official and third-party tutorials.

Finally, if you’re on the fence, you can download a trial from the official Affinity website and see if it meets your needs.

Happy editing! Here’s the finished image:

Date: 07/10/20; Version 3

Here is the path through Affinity Photo that I follow when preparing picture files for web pages, starting from either a scanned image or a digital camera picture. The tasks I need to carry out are:

- Read in a raw digital camera or scanned file.

- Convert and enhance the file for web use by

- Cropping and resizing

- Straightening

- Correcting perspective

- Correcting lens distortion

- Adjusting color, brightness and contrast

- Removing unwanted elements

- Sharpening

- Write out a file for use on the Web.

Affinity Photo has many features I don't use: some I don't need, others I haven't learned. These steps are what I have learned so far, by trial and error.

This note is based on Affinity Photo 1.8.3.

I used Adobe Photoshop to create graphics for web pages starting in 1994. I switched to Affinity Photo on the Macintosh in 2019 when Adobe insisted on selling Photoshop as subscription-only.

Steps

Here are the steps I use:

Affinity Photo Batch Resize

Open the picture in Affinity Photo.

Original image from a PhotoCD. This one is so dark I can't see to crop or straighten

The application opens up in the Photo 'Persona.' This seems to be adequate for photo enhancing. If you need to operate on RAW format files you use the Develop Persona.

For my camera, the application automatically detects my lens and zoom range from the EXIF data and compensates for lens-related barrel or pincushion distortion, and shows the camera in the heading bar above the picture. Supported lenses are listed at https://lensfun.sourceforge.net/lenslist/.

Straighten: I often have trouble keeping the horizon level in my photos. Choose the Crop tool and click the Straighten button in the heading bar. Then draw a horizontal or vertical line. Then click Apply.

Fix Perspective Distortion: (if necessary) This can occur if a photo isn't taken exactly square on to the subject. From the menus, choose Filters => Distort => Perspective.., or use the Perspective tool in the left sidebar. Drag the corner handles to square up the picture.

Crop the picture to focus on its strong points using the Crop tool in the left sidebar. I had to crop the example image because the PhotoCD image had fuzzy edges.

Straightening or Perspective fixes may create some light checkerboard areas on the edges: You can trim them off by cropping (select Mode: Original Ratio to preserve the picture proportions) or use 'inpainting' to fill them in. (The Affinity tutorial on Macros tells how to make a macro that does the inpainting. Check to make sure it worked.)

Curves. The right panel has a histogram and then a list of Adjustments. I use Curves to fix brightness, contrast, and black point. Clicking Curves causes a panel to pop up, sort of like the Photoshop version, showing a histogram of the picture and a diagonal line, the curve. Clicking on the curve creates a dot that can be dragged with the mouse to change the curve shape. If there are parts on the right where the histogram is zero or almost zero, pull the upper right corner to the left to eliminate these values from the gamut. If there are parts on the left where the histogram is zero or almost zero, pull the lower left corner to the right to eliminate these values from the gamut. This operation is basically the equivalent of an Auto Levels operation.

To bring out detail in the middle tones of a picture, lightening the whole picture at the expense of some detail in the highlights and shadows, pull the center of the curve up and to the left, making the curve into a concave-downward shape. This is often good for snapshots and flash pictures.

To increase the contrast in a picture, making the light areas lighter and the darks darker, making the curve take an s-shape by pinning the center and then pulling the upper half up. I use this to make shapes and patterns more dramatic.

Use the tool very cautiously.. a little motion has a big effect.

When done, Click Merge.

The picture after straightening, cropping, and curves.

Other editing. At this point, before resizing, do any other fixes that the image needs. To remove scanner dust, an unwanted wire, blemish, or background from the picture, use the many tools Affinity Photo provides. The Clone tool is especially useful here.

(At this point im my Photoshop pattern I invoke an Action that resizes and sharpens a photo. I have one for landscape photos and one for portrait orientation. Unfortunately, the way Affinity Photo's Macro facility works, I can't define the macros I want.)

Size the picture. Use Document => Resize Document... to resize the picture. Tell it to resample and use Bicubic sampling. Resizing should be done after the Curves operation, so that resampling will have an easier job. (Don't try to take a little picture and resize it bigger.) Set the DPI to 72 and the Units to pixels, make sure the lock between dimensions is clicked, and then input the width or height in pixels.. the other dimension will be calculated. When I can, I make two versions, one with picture dimensions twice the size of the picture's display area: see 'High DPI Pictures'.

Clarity. Filters => Sharpen => Clarity enhances color contrast in the midtones. (There is a nice video tutorial on it.)

Sharpen. Resizing may make the picture look blurry. Use Filters => Sharpen => Unsharp Mask and try different strengths.

Unsharp Mask control panel.

Export the picture. Choose File => Export and choose the output directory and file name. I save my gallery pictures as JPEGs, usually 100 quality.

Don't wipe out the original. Close the window and when it says the file was modified, choose 'Don't Save'.

on a hi-res display this should look sharper. See below.

Other Editing Tools

Affinity Photo Instagram Size

Contrast, Saturation, Vibrance

Some pictures scanned from film look washed out and are improved by increasing the contrast and color saturation a little. The Vibrance adjustment panel also has a Saturation slider.

Selections

It is possible to select just part of an image and apply different corrections to individual parts. One of the advice sites cautions that this may produce pictures that look unnatural: human perception is quite sensitive to mismatches between parts of a picture that should have the same illumination.

Output Files

Image Data

The .jpg files resulting from these editing steps in Affinity are different from those from Photoshop.

Compression is different between Affinity Photo and Photoshop. For one quality 60 file, the Affinity output file is 95051 bytes; the Photoshop version is 142448.

Metadata

I installed exiftool and jhead on my computer to investigate the metadata.

Affinity Photo Resize

Affinity Photo's Export function does not strip EXIF metadata out of its output image the way Photoshop's 'Save For Web and Devices' does. The exiftool output for Affinity images lists 123 values. For the same image from Photoshop, there are only 40 values.

I had set up Photoshop to add an IPTC comment with my name and copyright.. I forget how. Affinity Photo does not have this ability, but I can add copyright to my Affinity files with a shell command like

exiftool -artist='thvv@multicians.org' -copyright='(c) `date +%Y` Tom Van Vleck' filename.jpg

Image Thumbnails

For photo gallery pages, I often want a small thumbnail that image the user can click to open a big one. I make thumbnails with ImageMagick, a powerful package that contains many useful picture whacking tools: in particular, it provides the 'convert' command, which I use as follows:

convert -thumbnail x300 -resize '300x<' -resize 50% -gravity 'center' -crop '150x150+0+0' '-unsharp 0x6+0.5+0' +repage 'blah.jpg' ../thumbs/'blah.jpg'

I generate 150x150 thumbnails and show them in a 75x75 pixel space so the thumbnails look crisp on a retina screen.

To make an image look sharper on computers with a higher-resolution display

See a page on this subject. Bsically, save your picture with lots of pixels, and display it in a container with half the dimensions. Web browsers will figure out how to make it look crisp.

Copyright (c) 2019-2020 by Tom Van Vleck.

SE Stories | Mulvaney | Mushrooms | Photo | Borges